The halo may be the most readily recognized symbol in Christian art, and it is seemingly the simplest: a golden circle about the head, indicating sanctity. Yet this symbol has many variations over the centuries of Christian art. Some are stylistic, and I will say little about those except to note that I abhor the practice of depicting a halo in perspective, as a hovering ellipse. No one who has read my opinions on perspective in sacred art would be surprised by this. But some variations on the halo are significant, indeed ingenious. When drawing the Summula Pictoria, I intend to draw upon many of these significant variations, using them consistently in order to communicate much more than simple sanctity.

Not all halos are circular. Hexagonal (or less commonly octagonal and square) halos adorn the heads of allegorical figures representing the Virtues in many paintings of the late Middle Ages, such as the frescos that Giotto painted on the ceiling of the basilica at Assisi. I rarely draw purely allegorical figures in my religious art, and do not plan to do so in the Summula Pictoria except as background statuary; were I to draw them, I would use hexagonal halos. Several late medieval Italian paintings from the worksop of Bernardo Daddi give a hexagonal halo to St. Longinus; I have no idea why.

Mosaic of Pope John VII

Square halos appear in early mosaics, indicating sanctity on persons still living when the work of art was made. Usually this is a churchman, or whatever king or queen or emperor funded the building of the church that the mosaic adorns. In traditional Christian number symbolism, four represents the natural world and humanity, just as three represents the spiritual world and divinity. Their sum seven and product twelve represent the interaction of nature and spirit, and of man and God. The four sides of the square correspond to the natural quaternities: directions, seasons, elements, bodily humors.

Despite the fact that the square halo represents a lower order of holiness than the circular halo, it nonetheless bothers me. To place any artistic indication of holiness on a living man or woman, who has yet to be judged by God, seems presumptuous and sycophantic. Worldly honor may be due to a person for a great act of charity, such as funding the building a church. But the word of God is clear: Though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. Given how many persons presumed to be living saints proved, upon evidence revealed later, to be scoundrels, I would be happy to see this artistic practice abandoned altogether - or very nearly so.

I say very nearly so because I can think of two (and only two) persons on whom it would be appropriate. Two persons are alive today whom we may believe with confidence, based on the sacred scriptures and traditions, will be counted among the elect after their natural deaths: I speak here of the patriarch Enoch and the prophet Elijah. The former was taken by God, and the latter ascended to Heaven in the fiery chariot. Tradition identifies these two men with the witnesses in the 11th chapter of the Revelation to St. John, who will return from Heaven to prophesy in the reign of the Antichrist, suffer martyrdom, then rise from the dead and ascend into Heaven after three days. Thus, in the Summula Pictoria, I will depict Enoch and Elijah with square halos - and nobody else.

* * *

A curious sort of halo is characteristic of late medieval Spanish painting. It is a cusped octagon, seen for example adorning the head of St. Joseph in the Adoration of the Magi panel by Blasco de Grañén. In other panel paintings of this time, it appears on the heads of Ss. Joachim and Anna; of Simeon; of Abraham and Moses.

Adoration of the Magi, Blasco de Grañén

As fas as I can tell, this sort of halo was used only for saints of the Old Testament; that is to say, for holy persons who died before the Resurrection, whose souls descended to the Limbo of the Patriarchs and were present when Jesus Christ broke the doors of Hell and released its captives.

To the medieval mind, the distinction between saints of the Old Testament and saints of the New was important. In the occidental medieval Church, the former were rarely commemorated liturgically; this explains the absence, so to contemporary Roman Catholics, of specific devotion to St. Joseph before the late fifteenth century. According to the Golden Legend, a medieval encyclopedia of hagiographies,

It is worthy of note that the Eastern Church celebrates the feasts of saints of both the Old and New Testaments. The Western Church, on the other hand, does not celebrate feasts of saints of the Old Testament, on the ground that they descended into Hell - exceptions being made for the Holy Innocents, in each of whom Christ was put to death, and for the [seven] Maccabees.... The number seven is the number of universality. In these seven saints are represented all the Old Testament fathers who deserve to be celebrated.

I do not know why the octagonal halo for saints of the Old Testament was invented in 15th century Spain. I suspect it may be because many of the faithful at that time and place were converts from Judaism; these included Juan de Levi, the painter who trained Blasco de Grañén, and Esperandeu de Santa Fe, one of his major patrons. They perhaps gave more thought and care to the special manner in which persons such as Abraham were saved.

* * *

I do not plan to use the octagonal halo in the Summula Pictoria, but I do plan to use a distinctive halo for saints of the Old Testament. Here, I draw upon patristic writings in which the New Testament is associated with the clear light of the Sun. St. Ambrose calls Jesus Christ the Sun of Justice. To the saints of the New Testament, I give golden (solar) halos, each with an inner circle and an outer ring, with dark blue between them.

The Old Testament is associated with the uncertain and reflected light of the Moon. To the saints of the Old Testament, I gave silver (lunar) haloes; for these, crescents replace the outer ring, except on those who encountered the Sun of Justice face to face. Joseph, Simeon and Anna, Zachary and Elizabeth have fully circular outer rings on their halos. So do Adam and Eve before the Fall, and Moses who was present at the Transfiguration.

As I explained in my lecture Heavenly Outlook, the traditional perspective of Christian art is that of looking out of Heaven to things happening on the Earth; thus light sources and vanishing points are behind the viewer rather than within the picture. For this reason, I now draw the crescent moon halos on the patriarchs and prophets to the left - not to indicate a waning crescent, but to indicate a waxing crescent seen from the other side. As a waxing crescent, it indicates that the patriarchs and prophets are getting closer and closer to the revelation of the New Testament.

That one side of the Moon that is perpetually hidden from the Earth is an apt symbol for God’s relationship with the Gentiles during the Old Testament; His light shone on them as well, but nothing of it was specifically revealed to us on the Earth. For that reason, in those instances when a pagan, such as Nebuchadnezzar or the Tiburtine Sibyl, has a prophetic role in the Summula Pictoria, I draw the halo with a crescent moon facing the opposite way.

The assigning of halos to the saints of the Old Testament presumes some confidence that they are eternally saved; in most cases, the sacred scriptures and the liturgical and iconographic and patristic traditions support this confidence. In the cases of Samson and Solomon, the matter is not so simple; both men committed serious evils during their lives, and there is no biblical record of their repentance. In the 14th century, St. Mechtilde received a revelation that God had forgiven Samson and Solomon - and Origen as well - but chose to hide that forgiveness from men, lest others presume on their strength, wisdom, or learning to save them. Following that, I choose to give lunar halos to Samson and Solomon, but without the outer ring or crescent; in its place is the dark blue of the night sky, like a new moon that cannot be seen.

* * *

I have not yet mentioned the undoubtedly greatest saint of the Old Testament, John the Baptist, who of course is liturgically celebrated, and crowned with a halo in traditional Christian art, despite having descended to the Limbo of the Patriarchs.

St. John has a special place between the two Testaments; although he died before the Resurrection, he was cleansed from sinfulness at the time that he leaped in his mother’s womb. And in descending to the dead, he acted as a prophet and forerunner of the coming Savior, just as he did among the living.

The Virgin Mary also has a special place between the two Testaments; for this reason, she and John have their own special halos in the Summula Pictoria. Mary’s has a golden outer circle and a silver inner circle, with the light blue sky of day between them. John’s has a silver outer circle and a golden inner circle, with the dark sky of night between them.

* * *

The so-called cruciform halo is perhaps the most commonly used and best known variant of the halo, used to indicate a Divine Person - the Father, or the Son, or the Holy Ghost. It is a golden circle with a cross (often red) inscribed within it.

It was pointed out by some art historian - I forget which - that the notion that this halo is indeed cruciform is not altogether clear. On the person of Jesus Christ, the bottom part of the cross is obscured by His neck and body, and may perhaps not be there at all. Is the halo intended to indicate a cross, and thus refer to the Sacrifice on Calvary, or is intended to indicate the Holy Trinity, with three branches, not four?

I rather prefer the second interpretation, as it seems to make more sense when the Divine Person depicted is the Father or the Holy Ghost, neither of whom died on Calvary. In the Summula Pictoria, I draw the Father in the symbolic form of a hand, and the Holy Ghost in the symbolic form of a dove. In either, I draw three branches rather than four in the halo, not necessarily at right angles.

Mosaic of Jesus Christ at Ravenna. Made during the Arian rule of Theodoric the Ostrogoth. The cruciform halo was added later, when the church passed into orthodox hands.

* * *

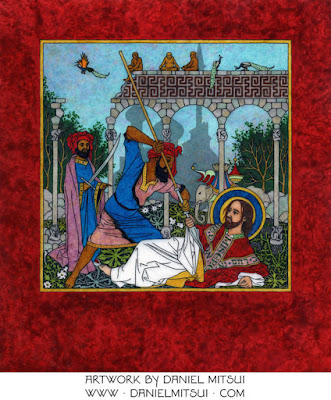

For angels, and for anyone who is divinely inspired - such as the Apostles at Pentecost, or the Evangelists writing their Gospels - I draw the outer ring blazing, with tongues of flame reaching upward. This kind of halo is common in Persian miniature painting. For the opposite - demonically possessed persons, such as Judas in his act of betrayal - the halo is black, the outer ring smoking rather than blazing. The black halo for Judas is not uncommon in Christian art - Fra Angelico uses it, for example, in his painting of the Sermon on the Mount. I am reserving it only for those events in which the sacred scriptures clearly indicate a demonic presence.

Sermon on the Mount, Fra Angelico

To indicate a person who is glorified, such as Jesus Christ at His Transfiguration, or after His Resurrection, I draw the halo radiant, with beams of light projecting from its outer ring.