(For those who don’t intend to read all of this, it is never to give up your intellectual property rights.)

In the past week, a few people have written to let me know about a new international art competition, run by the Fabric of St. Peter’s Basilica. The challenge is to create a new set of Stations of the Cross, and the prize is €120,000.

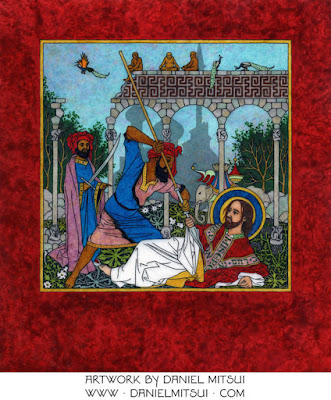

That sounded intriguing enough for me to investigate. (Although I imagine that those who know me well would chuckle at the thought of my artwork being displayed in St. Peter’s Basilica. If you want to know some of the reasons,

you can read this.

I am sorry to say that after reading the rules carefully, I not only decided against participating; I felt compelled to caution other artists against doing so. I find it annoying that so many (most, in my experience) art competitions are actually bad for artists. Especially since the reasons can be hard to see at first.

I will start by saying that this new competition from St. Peter’s does a couple of things well. It does not charge an entry fee. Usually, this is the first thing that makes me decline to participate. I dislike seeing organizations that claim to support the arts taking money from artists. I dislike seeing prize money rewarded that is collected from entry fees; that amounts to taking artists’ money and redistributing it amongst us. It doesn’t actually support the arts any more than a football pool would.

Thankfully, this new competition did the right thing; it secured funding from another source. The second thing I like is that it asks, as a first step, for artists to submit a portfolio and a CV. Those whose work is in line with what the judges want are then invited to submit a sketch. I actually like this a lot; it assures that artists who have no realistic chance of winning don’t waste their time preparing entries.

Some of you may remember a competition about six years ago, to design vestments for the World Meeting of Families in Dublin. I wrote a complaint about this also, here: https://www.patreon.com/posts/complaint-about-96263138. The most offensive thing about the WMOF competition was that the judges decided not to award the prize to ANY of the entrants, and instead to hire a liturgical arts company to design them.

No, I do not like them either, but that is not the point. The point is that this is what the WMOF wanted all along, and instead of just going to the company with their instructions in the first place, they dangled prize money in front of artists all over the world, hoping that one of them would guess correctly what they already had in mind. What a complete waste of their valuable time that turned out to be.

So at this point, the contest sponsored by St. Peter’s Basilica looked promising. Sure, I thought to myself, it would be something of a departure; I specialize in small ink drawings, and the winner is required to produce fourteen panels, each four feet square, in just over 14 months. So that would require new materials, a new workspace, and a different stylistic approach — there is no way that I would be able to draw at the level of detail that I usually do and produce a picture that large per month. But €120,000 is much more than I normally make over 14 months… If I work on this project and only this project, postpone all other commissions and speculative work until 2026, rearrange the basement into a painting studio, I could probably figure something out. At the end of it, I would have a set of major works that I could try to sell elsewhere, and which might generate a lot of print sales also. And I know, from experience, that working for big ecclesiastical institutions does get attention. When I was hired by the Vatican to illustrate an edition of the Roman Pontifical in 2011, it did a lot to establish my professional reputation.

Then I kept reading, and realized: Oh wait, they intend to keep the paintings, don’t they?

At this point I sighed and realized that the artists who enter are not competing for a prize. They are competing for a commission. This money isn’t being given out as a bonus; it’s being given out as payment for the artwork.

Now believe me, I have no problem with receiving commissions. But they aren’t prizes, not any more that any other exchange of goods or services for money is a prize. Now I started doing a different set of calculations: €120,000 means approximately $9,405 for each 4’ × 4’ painting. That is… not necessarily a lot.

Look, I know that there are all sorts of different factors that determine the pricing of artwork. My own rates are calculated per-square-inch. Considered by area, they are higher than many other artists’ because my work is minutely detailed. But I try to price my work as low as possible, because I don’t want to be beholden to a few wealthy patrons. I like that most of my patronage comes from people of ordinary means. My ink drawings aren’t cheap, but they cost about the same as tattoos of comparable size and intricacy. And people of ordinary means can afford tattoos - just look around.

If I were asked what sort of picture I could make, at my usual level of detail, for a fair cost of $9,405, I might answer: a drawing in black ink measuring a little less than 15" × 15", centered on a larger piece of paper. (Maybe that seems expensive, but it’s about what an artist with 20 years of experience and a good reputation would charge for a full back tattoo on a very large man.)

I know that there are plenty of artists who work in looser, more abstract styles who can fill a 4’ × 4’ canvas much faster than I can fill a piece of paper. Some people like that kind of art. But most of the painters whom I admire would, I think, be selling themselves short to accept a commission like this one.

And then, I read that the winner of this competition will only receive €20,000 in advance. How exactly is he supposed to pay his rent and feed his family during the time it takes to make fourteen big paintings? Who could afford to win this, except someone who is independently wealthy, or who paints so quickly that he can finish them all in a few months?

Then, I read that the Fabric of St. Peter’s Basilica requires, from the winner, “A formal deed of unconditional assignment of the Via Crucis, including the relative rights of use and exploitation of the work, without any constraint whatsoever”. After this, I was no longer just annoyed; I was angry.

Sometimes young or aspiring artists come to me for advice. There is one thing that I tell all of them. Please pay attention to this: If you an independent artist, making original, non-derivative work, never give up your intellectual property rights.

Never, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, give up your intellectual property rights.

Ever.

To anyone. Not to a patron, not to a publisher, not to a pope.

If anyone asks you to sell, transfer, or relinquish the copyright to your artwork, say politely that you never do this, but that you are willing to negotiate a license for the purposes he requires. Most patrons and publishers will accept this and work out the license with you. Avoid doing business with anyone who pushes back and insists on getting the copyright from you.

The intellectual property rights to a work of art are more valuable, in the long run, than the work itself. They may be the most valuable things, in monetary terms, that you will ever own. They are what allow you to protect the integrity of your artistic vision. They are what allow you to generate passive income from your existing work, in the form of derivative works, prints, merchandise, or licenses for reproduction. And they can continue to do this for you for the rest of your life, and for your heirs long after your death (for seventy years, if you are an American). For an independent artist, the rights to your intellectual property are one of the only legal or economic advantages in your line of work. They function like your investment portfolio, your retirement fund, your legacy, your life insurance.

That anyone running a contest would ask an artist to give this away offends me. Presenting it as a condition of a prize (something that the artist should be honored to receive) strikes me as absurd. If a commission were offered to me, personally, with the same terms as this supposed prize, I would decline it immediately.

Finally, I will repeat a little of what I wrote after the WMOF competition. Art competitions don’t have to be like this. They can be fair and beneficial to everyone involved. Here are the things that I would like anyone who intends to hold one to keep in mind:

1. A competition does not inspire creativity; it merely diverts it. I imagine that some organizers of competitions, when looking at the submitted entries, think to themselves: “How wonderful that we were able to help bring all this new artwork into being!” Sorry, but no. Artists, generally, have more ideas than they have time to realize. They do not sit around idle, making nothing, until a competition is announced. The time and effort put into a competition entry is time and effort that is not put into another project. That other project may very well be more artistically excellent, more personally fulfilling, or more lucrative.

2. Paying someone fairly for his work is an obligation, not a prize. That is to say, if the prize to the competition amounts to no more than the cost of buying the winning work, it is not so much a competition as a job application process. Which is fine, but please be forthright and present it as such.

3. It is wrong to ask job applicants to complete a task for which they will be hired (or a large part of it) before they know if they will be paid. If you want to know whether job applicants are well-suited to the task, you should determine that using the same means that any honest employer uses. You can ask for portfolios; you can ask for résumés; you can ask for interviews. Do not ask for free work.

4. If you are giving an actual prize (which is to say that the winner gets the money AND keeps his art to sell) then you are justified in asking artists to submit something brand new to the competition. But the artists should have the possibility of profiting from their work even if they lose. If the artwork that you ask them to submit is so specific to your own purpose, organization, or event that it has no chance of being sold on speculation, then you really should not hold a competition. Instead, you should find an artist whose modus operandi includes making drafts and revisions, and hire him for the job.

5. The artists should get some creative fulfillment from their work even if they lose. If you have such a specific idea in mind for the winner that you need to include a lot of detailed instructions about how the entrants should approach the project, then you really should not hold a competition. Instead, you should find an artist who is willing to collaborate with you to realize a project over which you exercise artistic control. The entrants should not be asked to forgo both artistic control and the certainty of payment.

6. The artists should get some publicity for their effort even if they lose. Display the entries, or a least the finalists, after deciding upon a winner. This will also hold you accountable for making a good decision.

7. Promise to give out the prize. If you are concerned that there will not be enough entrants, then do more to attract them to the competition. That no artist will give you exactly what you want is the risk that you assume when you hold a competition. The entrants should not be required to assume that risk instead.

8. Do not charge an entry fee. If the artists are providing the work, then the money should flow to them, not the other way. If you are using the entry fees to subsidize the prize, then you are just making the money flow about the pool of entrants, not into it. If you have no money to give away — don’t hold a competition until you have raised some. That is what organizations that support the arts are supposed to do: raise funds to give to artists, or to spend on things that actually benefit them. If you only have a little money, know that offering a little prize is better than taking money from artists in order to offer a big one.

9. But first, cover the expenses associated with entering and winning the competition, such as postage, return postage, and framing. Make it reasonably easy, convenient, and costless for artists to participate.

10. Do not make any claim on the intellectual property of the submitted artwork, whether it wins the prize or not. If you want a license to use the artwork for specific purposes, negotiate that separately.